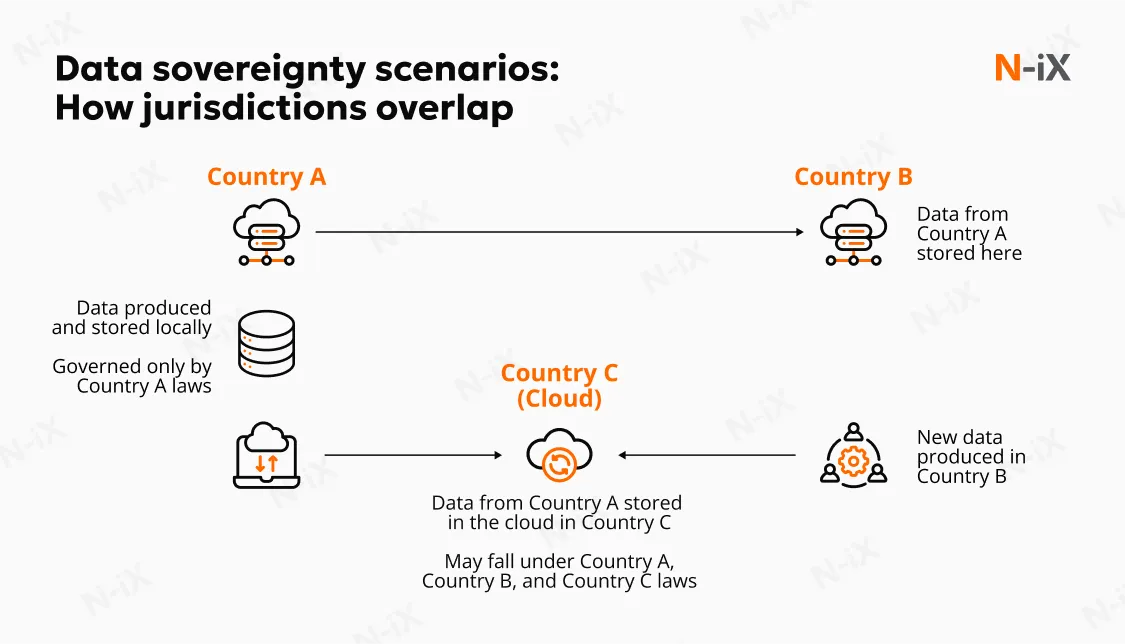

Enterprises adopt global cloud platforms to gain speed, scale, and flexibility. But with this came a new vulnerability: the realization that storing data in one country doesn't prevent it from being subject to another country's laws. This tension gave rise to data sovereignty, the principle that information must remain under the jurisdiction and governance of the region where it resides. The focus has evolved from simply asking where data resides to examining who holds the power to access it, demand its disclosure, and regulate its use.

Data sovereignty appeared as a direct response to the risks created by the globalization of data storage and cloud adoption. Companies realized that keeping data "in-region" wasn't enough because laws like the US CLOUD Act allow foreign authorities to reach across borders. At the same time, new EU data sovereignty regulations, such as DORA, hold organisations accountable for control, resilience, and auditability.

In this article, we will define data sovereignty concept, how it works in practice, and the regulatory drivers shaping data governance. It explores the frameworks that define sovereignty, outlines a six-step approach for day-to-day enforcement, examines the most common challenges organisations face, and highlights how to navigate them effectively.

What is data sovereignty?

Data sovereignty is the principle that information is governed by the laws and regulations of the country or region where it originates, is collected, processed, accessed, or stored. For enterprises, this means that legal frameworks, not internal preferences or corporate policies, define how data may be used, shared, or transferred. If consumer information is collected in Europe, for instance, it falls under the jurisdiction of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), regardless of where the organisation is based.

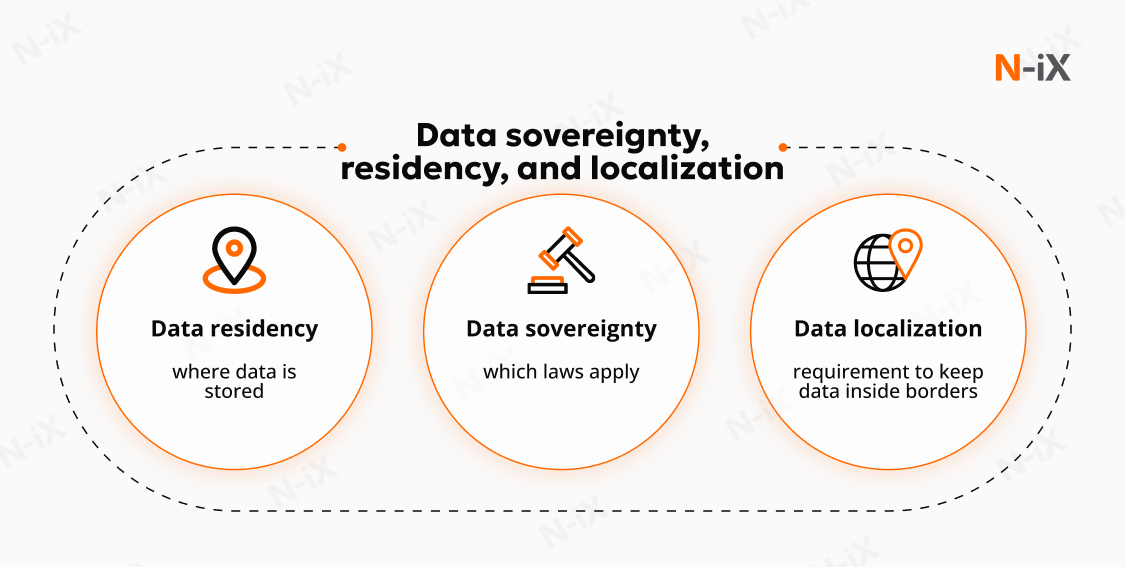

The data sovereignty definition is closely tied to broader concerns about privacy, government access, security, international competition, and even fundamental rights. While often used interchangeably, data sovereignty, residency, and localization describe different obligations that carry very different implications:

- Data sovereignty establishes the legal authority that governs information. Data collected in one jurisdiction must remain subject to its rules, even if stored elsewhere.

- Data residency refers only to the physical location of storage or processing. For example, information held on servers in Germany is subject to German and EU jurisdiction, regardless of where the data was initially generated.

- Data localization requires that specific categories of data remain within the borders of the country or region where they were collected. This tendency is often driven by national security priorities or efforts to protect privacy and domestic digital economies.

For multinational organisations, misunderstanding these differences can lead to exposure. For instance, assuming residency guarantees sovereignty has already resulted in compliance failures where regulators deemed companies in violation despite data being hosted in the region.

Choose the right EU sovereign cloud provider—get the report!

Success!

How does data sovereignty work?

Data sovereignty works by combining legal frameworks with operational and technical safeguards that ensure information remains under the control of the jurisdiction where it originates. It is not a single policy or technology but a layered approach that aligns regulation, infrastructure, and governance. At its core, sovereignty means that data collected in one country must remain governed by that country's rules, regardless of where it is stored or processed. To enforce this principle, enterprises and regulators have built a framework around three interconnected dimensions: data, operational, and digital sovereignty.

At the core, sovereignty begins with the legal framework. Data collected in a jurisdiction is subject to its laws, regardless of where it is later stored or transferred. It also means compliance strategies must account for local privacy regulations and extraterritorial claims, which can undermine the effectiveness of simple "in-country" storage. Legal oversight defines the boundaries, but must be matched with operational and technical measures to ensure those rules are enforceable.

Operational sovereignty extends this concept to the day-to-day management of infrastructure. It ensures that the systems underpinning sensitive workloads remain resilient, available, and governed by the local authority. Business continuity planning, disaster recovery capabilities, and local administration of critical systems all form part of operational sovereignty.

Digital sovereignty takes the principle further, focusing on control of digital assets themselves. Effective governance requires clear, enforceable rules over who can access what, under which circumstances. Policy-as-code approaches and auditable workflows allow it to embed sovereignty into technical operations rather than relying solely on manual oversight. Organisations must be able to track access and prove to regulators and customers that sensitive data is handled in line with local law.

The cloud environment adds another layer of complexity. Public cloud deployments can support sovereignty requirements if workloads are kept within approved regions and subject to local governance. However, the distributed cloud model, where organisations leverage local providers or even on-premises infrastructure, often offers greater certainty. By keeping workloads closer to the jurisdiction of origin and maintaining stricter control over administration and encryption keys, sovereign cloud reduces exposure to extraterritorial claims and compliance conflicts.

What are the regulatory drivers of data sovereignty in 2026?

Simply put, data sovereignty is determined by the legal frameworks of the jurisdiction where information is generated, collected, or stored. These frameworks establish the authority to dictate how data may be used, who can access it, and under what conditions it can be transferred or shared.

In many cases, a single dataset can fall under multiple overlapping regimes. Under this view, data generated in one jurisdiction but stored or processed in another is instantly subject to the rules of both. This dual obligation requires organisations to adopt safeguards such as contractual data protection agreements, standardized transfer mechanisms, encryption, and key management to satisfy regulators in each territory.

But that's only the tip of the iceberg; effective sovereignty management demands continuous awareness of regulatory developments across all operating regions. Companies storing or processing information in multiple jurisdictions must remain current on data protection laws, cross-border transfer restrictions, and specific requirements tied to sectors such as finance or healthcare. Below are the most significant data sovereignty regulations that redefine sovereignty and its operational implications.

Foundation of EU data rights: GDPR

The EU's ambitions extend beyond compliance frameworks such as GDPR and the Data Act. The European Commission, in its 2020 Communication on a European Strategy for Data, formally set out the concept of "digital sovereignty," aiming to create "a single European data space" where information is "stored, processed, and put to valuable use in Europe." [1]

Data sovereignty GDPR establishes personal data protection as a fundamental right and extends its reach beyond Europe's borders through extraterritorial applicability. The regulation obliges organisations to maintain lawful processing, minimise collection, provide individual rights such as access and erasure, and restrict cross-border transfers unless the destination country ensures "adequate" protection.

The Schrems II judgment further tightened these rules by invalidating Privacy Shield and demanding supplementary safeguards even where Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs) are used. GDPR makes sovereignty less about physical storage and more about legal authority: European data must remain governed by EU law, wherever it resides.

Financial resilience under EU oversight: DORA

Effective January 2025, the Digital Operational Resilience Act (DORA) applies to banks, insurers, investment firms, and any third-party ICT providers deemed critical to financial services. Its requirements go well beyond data protection, mandating resilience, auditability, and regulator access to ICT systems. The European Banking Authority (EBA), as part of the European Supervisory Authorities, has explicitly emphasized the need for "full control and oversight of critical outsourced functions," underscoring why sovereign cloud models are increasingly seen as essential for compliance and risk management [2]. By 2028, industry forecasts suggest that 60% of financial services firms outside the US will adopt sovereign cloud environments to comply with DORA and related data sovereignty regulations [2].

Businesses must maintain systems that are continuously auditable, secure, and accessible to regulators. Unlike earlier frameworks focused narrowly on data protection, the Digital Operational Resilience Act establishes a regulatory obligation for financial institutions to demonstrate resilience, audibility, and regulator access across all digital operations. This requirement compels organizations to map regulatory controls directly to ICT workloads and ensure that every infrastructure layer can withstand scrutiny. The EU Digital Operational Resilience Act closes gaps where third-country operators or cloud providers could bypass local oversight within data governance in banking and finance services.

Moreover, the Digital Operational Resilience Act for financial services is not limited to where economic data is stored. Institutions must maintain ICT systems that are continuously available, secure, and transparent to regulators, even under severe disruption. DORA extends to business continuity and disaster recovery (BCDR) requirements, which confirm that critical financial services can continue without interruption during regional outages or systemic shocks.

A key practical element of DORA is identifying high-risk data and workloads. Core banking systems, investment platforms, and insurance operations are among the areas where resilience gaps would have the most systemic consequences. For these, sovereign cloud adoption provides jurisdictional control, locally governed administration, and customer-managed encryption keys.

Critical infrastructure and industry obligations: NIS2 Directive

The NIS2 Directive, transposed by Member States in October 2024 and entering enforcement through 2025, extends cybersecurity obligations to a broad spectrum of sectors: energy, healthcare, transport, digital infrastructure, and public administration, among others. The regulation demands rigorous risk management, incident reporting within tight deadlines, and liability at the management level. From a sovereignty perspective, NIS2 places national authorities in direct oversight of data and systems underpinning critical functions. It links sovereignty to resilience of essential services, ensuring that sensitive operational data and security processes remain visible and enforceable within the jurisdiction.

Access and portability beyond personal data: EU Data Act

Becoming applicable on 12 September 2025, the EU Data Act redefines sovereignty by addressing non-personal and industrial data. It introduces rights for users to access and port data generated by connected devices and prevents providers from using vendor lock-in practices that restrict switching between cloud services. It prohibits unlawful third-country access to non-personal data stored or processed in the EU. It underscores that sovereignty extends beyond personal information to cover industrial, IoT, and operational datasets.

Jurisdiction without borders: US CLOUD Act

The Clarifying Lawful Overseas Use of Data (CLOUD) Act illustrates why physical location alone does not guarantee sovereignty. It authorizes US authorities to compel disclosure of data held by US-based providers, regardless of where that data is physically stored. This extraterritorial reach directly conflicts with other nations' sovereignty efforts, particularly in the EU and Asia, and has become a catalyst for sovereign cloud initiatives. Organisations seeking to mitigate the risk of conflicting obligations increasingly adopt US data sovereignty laws, including customer-managed encryption keys, jurisdiction-specific hosting, and split-control architectures.

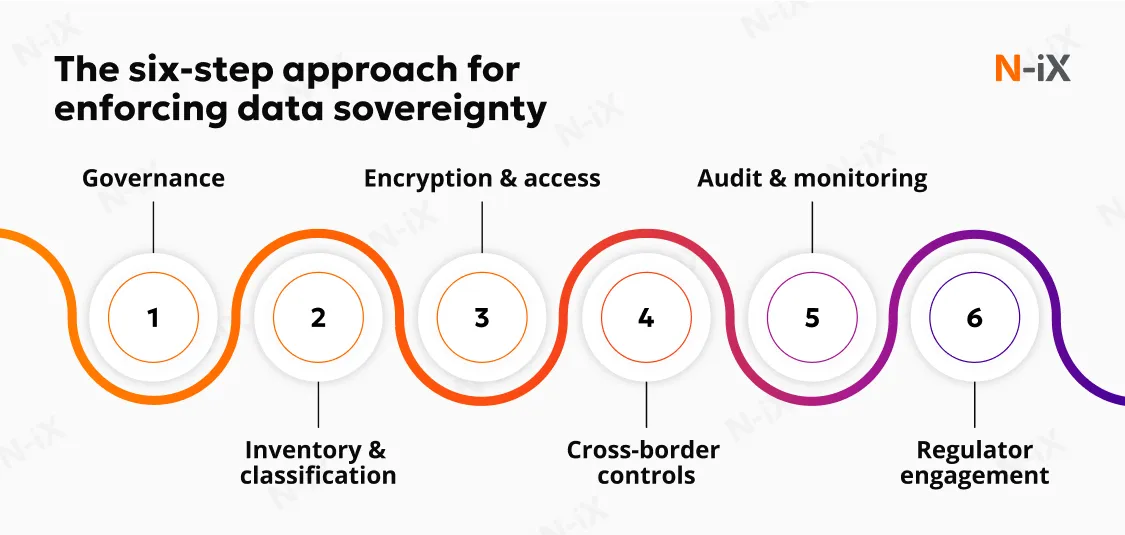

The six-step approach for enforcing data sovereignty

Enforcement happens daily across governance, technology, and operations, and it is increasingly tied to audit expectations in finance, healthcare, manufacturing, and public services. Let's discover how.

1. Governance and control as daily practice

The first step in enforcement is data governance implementation. Companies establish clear rules for classifying, storing, and accessing data. These rules are part of a living framework: updated as laws change, embedded into onboarding processes, and checked through regular reviews. Decision-making is escalated to the board when sovereignty affects market access or introduces exposure to fines.

2. Knowing what data exists and where it resides

Sovereignty requires knowing the complete picture of data assets. Enterprises maintain inventories that tag datasets with their sensitivity (personal, financial, health, or intellectual property) and residency (where they are stored or processed). This tagging enables automation: orchestration tools block data transfers to non-compliant regions, and dashboards track where regulated data resides. Without such visibility, sovereignty collapses into guesswork, exposing companies during audits or legal disputes.

3. Technical enforcement through encryption and access control

The strongest policies mean little without technical guarantees. Sovereignty is enforced through encryption at rest and in transit, with organisations retaining custody of encryption keys. Models such as "hold your own key" or "bring your own key" prevent cloud providers or foreign governments from unilaterally accessing data. Identity and access management frameworks reinforce control: zero-trust verification, least-privilege assignments, and continuous monitoring of privileged users reduce the risk of unauthorized access.

4. Managing cross-border transfers

Global operations inevitably involve data moving across borders. Enterprises manage this risk through strict transfer mechanisms, such as Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs), adequacy decisions, or binding corporate rules. Hybrid and multi-cloud strategies help balance these requirements: critical workloads remain in sovereign environments, while less sensitive workloads leverage global public cloud for efficiency. Sovereignty, therefore, shapes infrastructure design as much as data sovereignty compliance policies.

5. Monitoring, audit, and regulatory readiness

Control without evidence is noncompliance by another name. Security and platform teams maintain immutable, time-synced logs for admin actions, data access, key operations, and configuration changes. Enterprises use continuous monitoring tools to track data access, detect anomalies, and log every transfer or privileged action. These records create the audit trails regulators expect under frameworks like the Digital Operational Resilience Act. Internal and external audits stress-test the system, revealing weaknesses before they become liabilities. Sovereignty is measured by the ability to produce clear, regulator-ready evidence on demand.

6. Legal expertise and regulator engagement

Finally, sovereignty enforcement depends on legal and data sovereignty compliance expertise embedded in daily operations. Legal teams interpret new requirements, assess conflicts between extraterritorial laws, and ensure contracts reflect jurisdictional realities. Proactive engagement with national data protection authorities helps avoid missteps and strengthens trust with regulators. For global businesses, in-country legal partners provide essential guidance where local interpretation diverges from international norms.

Common challenges enterprises face with data sovereignty

Navigating sovereignty is rarely straightforward. Even well-prepared organisations encounter obstacles from overlapping regulations, extraterritorial pressures, and compliance's technical and financial weight. So, what are the most pressing challenges that make enforcing data sovereignty difficult in practice?

- Confusing data residency with sovereignty, handling storage location as compliance when legal jurisdiction is broader.

- Exposure to extraterritorial laws, such as the DORA, undermines local protections.

- Overlapping and conflicting jurisdictional requirements across regions.

- Complexity of managing cross-border transfers under frameworks like SCCs and BCRs.

- Limited feature parity and higher costs in sovereign cloud regions.

- Vendor lock-in and weak exit strategies for regulated workloads.

- Shortage of skilled personnel with jurisdiction-specific security and compliance expertise.

- High compliance costs from audits, encryption, monitoring, and legal oversight.

These challenges illustrate why sovereignty is not solved by technology alone but requires governance, operational discipline, and regulatory awareness. Facing and overcoming them is possible with skilled partners such as N-iX, who combine compliance expertise, engineering capability, and cross-industry experience to help enterprises meet sovereignty requirements while maintaining resilience and scalability.

Conclusion

Data sovereignty's future will be marked by increasing complexity as jurisdictions tighten controls, expand their regulatory reach, and impose new obligations on enterprises and technology providers. Sovereignty is about control-and control must be demonstrable to regulators, transparent to stakeholders, and enforceable in practice. All of this raises a practical question: How do you build a sovereignty strategy that is compliant, resilient, and future-ready?

N-iX can be your strategic data sovereignty partner. We work with enterprises across regulated industries to align legal obligations with technical safeguards and operational practices. Our teams help design architectures, implement governance frameworks, and verify that sovereignty requirements support long-term digital transformation.

FAQ

What is the primary purpose of data sovereignty?

The primary purpose of data sovereignty is to ensure that information remains under the legal authority of the jurisdiction where it originates. By doing so, governments protect the privacy and rights of individuals, maintain national security, and support economic competitiveness by controlling how sensitive or strategic data can be stored, accessed, or transferred.

What are data sovereignty solutions for businesses?

Data sovereignty solutions are practical measures that organizations adopt to ensure their data remains governed by the jurisdiction's legal framework where it originates or is stored. In practice, this often combines strong governance policies, technical controls such as "hold your own key" (HYOK) or "bring your own key" (BYOK) encryption models, and region-specific hosting. Enterprises also rely on contractual safeguards like data processing agreements, supplemented by continuous monitoring and audit practices to demonstrate regulatory compliance.

What are data sovereignty requirements?

Data sovereignty requirements vary across jurisdictions but typically include strict rules on how personal or sensitive data is collected, stored, processed, and transferred. Business organizations must comply with local data sovereignty laws governing data residency, cross-border transfers, consent management, encryption standards, and auditability. In many cases, they must demonstrate operational resilience and transparency to regulators.

What is the difference between data sovereignty vs residency vs localization?

Data residency refers to the physical location of data storage, while data localization requires certain information to remain within national borders. Data sovereignty, however, is about legal authority. Even if data is stored in one region, it must comply with the jurisdiction's laws where it originated, making sovereignty broader and more complex than simply knowing where data sits.

What are the main data sovereignty laws by country?

The EU enforces GDPR, DORA, NIS2, and the upcoming Data Act, raising privacy, resilience, and oversight standards. In the US, the CLOUD Act asserts extraterritorial reach, while state laws like the CCPA and CPRA regulate personal data use. China has established strict localization and security requirements through its Cybersecurity, Data Security, and PIPL laws.

References

- Data Sovereignty: From the Digital Silk Road to the Return of the State

- Sovereign Cloud Implications for Financial Services CIOs - Gartner

Have a question?

Speak to an expert