It is difficult to imagine a modern enterprise without operational data systems and analytical reporting. Applications, digital products, customer interactions, and internal processes all rely on reliable data storage, processing, and access. At the same time, leadership depends on the same data to assess performance, track trends, and make informed decisions. This dual reliance is what makes the distinction between a database vs data warehouse crucial.

The overlap can seem reasonable. Both systems store data. Both support reporting in some form. Both are foundational to enterprise IT. But as organizations scale, diversify their data sources, and expand analytical use cases, these similarities begin to fade. What initially appears to be a matter of storage or performance gradually becomes a question of architectural responsibility: which systems are intended to support real-time operations and which to support consistent, long-term analysis.

This is often the point at which companies begin to reassess their data foundations, sometimes independently, sometimes with the support of data warehouse consulting, to reduce ambiguity and address operational and analytical needs. Let's take a moment to discuss some of the key characteristics of a data warehouse vs database.

What is a database?

A database is an organized system for storing and managing structured or semi-structured data so that applications can operate reliably in real time. It sits at the core of most digital systems, supporting the continuous flow of transactions that keep products, services, and internal processes running. Every time an order is placed, a payment is processed, or a user profile is updated, the database records the change accurately and immediately.

Databases are built with a clear priority: maintain the current state of a system while handling a high volume of small, fast operations. Their role is not analytical interpretation or long-term trend analysis, but operational continuity. This design focus shapes how databases are structured, accessed, and scaled within an enterprise environment.

Core principles of a database

To fulfill this role, databases share core characteristics that emphasize transactional reliability and real-time access.

- Transactional focus: Databases are optimized for Online Transactional Processing (OLTP). They handle large numbers of short, simple operations such as inserts, updates, and deletes, often executed concurrently. The goal is predictable performance and low latency under constant load.

- Strong data integrity guarantees: Most transactional databases adhere to the ACID (atomicity, consistency, isolation, and durability) principles. These properties ensure that each transaction is processed completely and correctly, even in the presence of system failures or concurrent access.

- Concurrency and availability: Databases are engineered to support multiple users or application processes accessing the same data simultaneously. Locking, isolation levels, and replication mechanisms are used to balance performance with correctness.

- Focus on current state: A database typically represents the latest version of data required to run an application. Historical states may be retained, but they are not the primary concern unless explicitly designed into the schema.

- Managed through a database management system: Interaction with the data is handled by a DBMS, which controls access, enforces rules, and manages security.

How a database works in practice

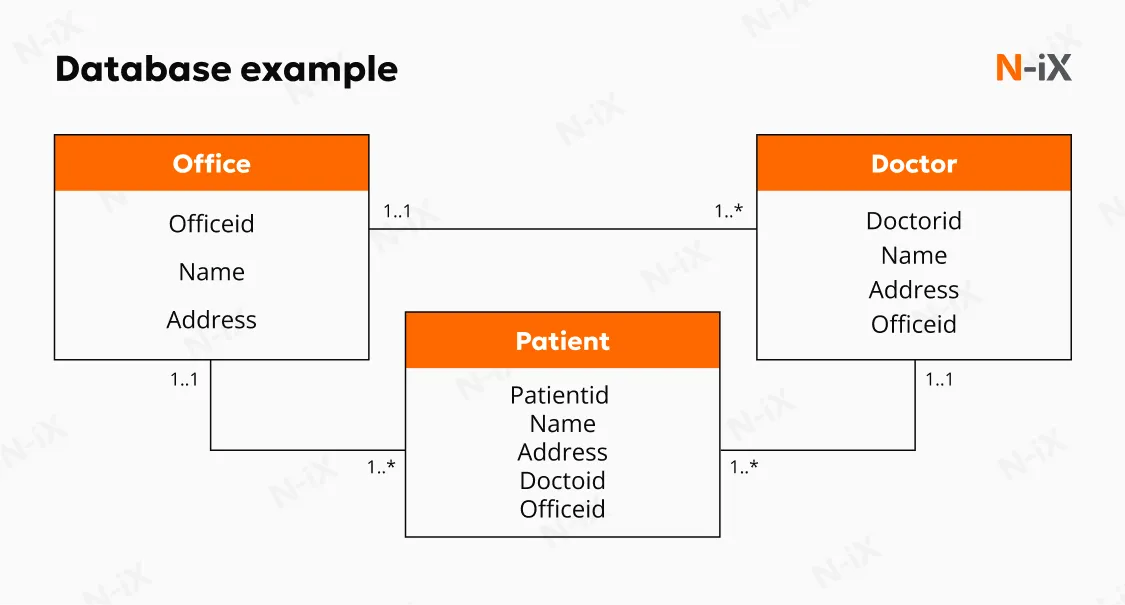

Within an enterprise architecture, databases form the operational data layer. Databases generally fall into two broad categories, each aligned with different application needs. Relational (SQL) databases store data in structured tables with predefined schemas. Relationships between entities are explicitly defined through keys, which support consistency and complex transactional logic. Another type is Non-relational (NoSQL) databases, designed to accommodate flexible data structures and scale across distributed environments. They handle documents, key-value pairs, wide columns, or graphs, making them suitable for use cases where schema rigidity would slow development or limit scalability.

Databases are tightly coupled with applications and optimized for performance and data integrity. While they may support basic reporting or operational dashboards, their structure and workload profile make them unsuitable for complex analytical queries at scale. For that reason, databases are commonly paired with downstream systems, such as data warehouses, that handle historical analysis and cross-system reporting without disrupting operational workloads.

Typical database use cases

Databases are used wherever systems must respond immediately to events and ensure that each change is recorded accurately. Their role is to support continuous business operations, where data is created, updated, and accessed in real time as part of ongoing processes rather than through retrospective analysis.

- Processing customer transactions: Databases underpin transactional workflows, including payments, bookings, account updates, and order placement. In these scenarios, each operation must be completed reliably and in the correct sequence.

- Managing inventory and order fulfillment: Inventory levels, shipment statuses, and fulfillment workflows depend on databases to reflect the current state of goods and orders at any moment.

- Supporting user authentication and profile data: User accounts, credentials, permissions, and session data are typically stored in databases optimized for frequent reads and writes, with strong access controls.

- Powering operational applications and services: Core business applications, such as CRM systems, ERP platforms, and internal service tools, rely on databases to manage the data they operate on.

What is a data warehouse designed to do?

A data warehouse is a centralized data system designed to support analytical processing, reporting, and decision-making across an organization. Unlike operational databases, which are optimized to record and update data as business events occur, a data warehouse is built to consolidate data from multiple sources, preserve it over time, and make it suitable for analysis at scale.

Its primary role is to provide a consistent analytical foundation. Data from operational systems, such as transactional databases, CRM platforms, ERP systems, and external feeds, is collected, aligned, and stored in a structure that supports comparison, aggregation, and historical analysis.

Core principles of data warehouse

The design of a data warehouse reflects its analytical purpose and differs in several critical ways from operational data systems.

- Subject-oriented organization: Data is structured around business subjects such as customers, sales, products, or finance, rather than around individual applications.

- Integrated data from multiple sources: A data warehouse reconciles data originating from different systems by standardizing formats, naming conventions, and reference data.

- Time-variant data: Historical data is a core feature. Warehouses typically store data snapshots over extended periods, allowing organizations to analyze change, trends, and performance over time rather than focusing only on the current state.

- Non-volatile structure: Once data is loaded, it is generally not updated or deleted in day-to-day operations. Data warehouse strategy supports consistent reporting and reduces ambiguity when results are revisited or audited.

- Optimized for analytical workloads (OLAP): Data warehouses are designed to execute complex, read-heavy queries that scan large datasets, aggregate metrics, and join multiple dimensions. Performance is optimized for analysis rather than for high-frequency updates.

Data lake vs data warehouse—discover which option is right for you!

Success!

How a data warehouse works in practice

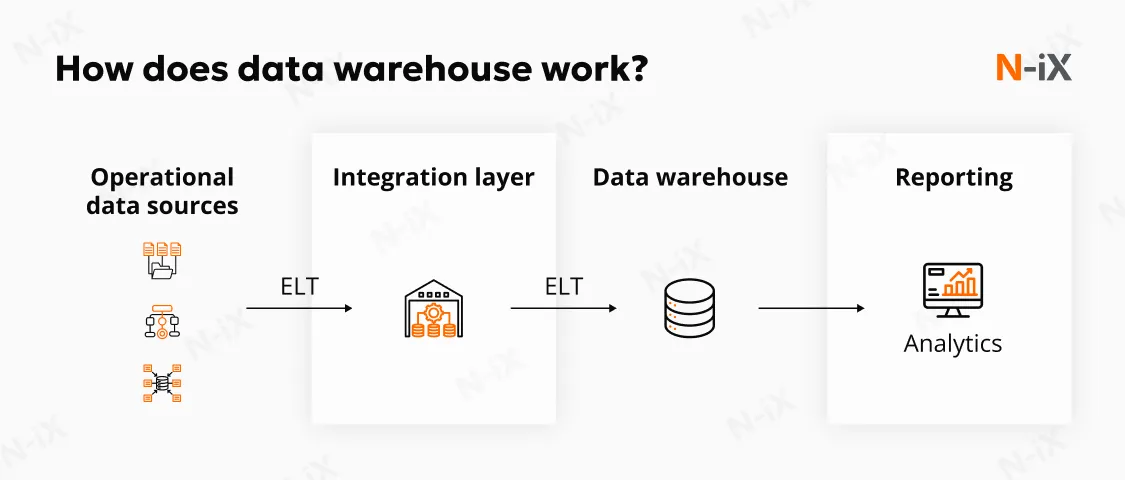

From an architectural perspective, a data warehouse sits downstream from operational systems and serves as a dedicated analytical layer. Data is periodically ingested from source systems through extract, transform, and load (ETL) or extract, load, transform (ELT) processes. During this step, data is validated, standardized, and reshaped for analytical use. The warehouse typically stores data in denormalized structures, often using dimensional models such as star or snowflake schemas, which simplify querying and improve performance.

Modern data warehouses frequently use column-oriented storage and scalable compute resources to process large analytical queries. These design choices allow analysts and reporting tools to scan only the data needed for a given query. In comparison to a data warehouse vs transactional database, it doesn't read entire records as OLTP systems do.

Real-world use cases from N-iX experience

In large, distributed technology environments, data warehouses are often introduced when organizations need to understand cost and performance beyond the limits of individual platforms. In one engagement delivered by N-iX, a global technology company undergoing a cloud migration, the client lacked a unified view of infrastructure usage and spending.

We consolidated a centralized data warehouse for billing data, infrastructure telemetry, and operational metadata from multiple cloud environments into a single analytical layer. These actions enabled tracking of cost drivers across services, teams, and regions over extended periods, rather than relying on isolated reports.

Another recurring scenario occurs in supply-driven organizations that generate large volumes of operational data across heterogeneous systems. In a separate engagement, we worked with a leading industrial supply company that required analytics across procurement, logistics, inventory, and sales systems operating at scale.

A data warehouse was implemented as the central analytical platform, integrating data streams from multiple operational systems and structuring them for large-scale analysis. Our data warehouse automation services enabled consistent reporting across business functions and supported advanced analytics use cases that depended on historical depth and cross-system correlation.

How do data warehouses and databases differ?

Databases and data warehouses often coexist within the same data ecosystem, yet they are designed around different assumptions about how data will be used. The distinction becomes clear when looking at how each system handles workload, time, structure, and access. These differences shape technical behavior and the reliability with which data can support day-to-day operations and longer-term analysis.

1. Core operational paradigms

At the operational layer, databases support Online Transaction Processing. Their primary responsibility is to handle a continuous stream of short, discrete operations, such as inserting, updating, or deleting individual records, while maintaining strict consistency guarantees. These systems are designed to enforce ACID properties, ensuring that each transaction is processed reliably even under high concurrency. This model supports use cases where correctness and immediacy are critical, such as payment processing, order management, or account updates.

At the analytical layer, data warehouses support Online Analytical Processing. Instead of managing individual transactions, they are built to execute complex queries that scan large volumes of data, aggregate metrics, and evaluate patterns across dimensions and time. Query execution is optimized for throughput rather than latency, enabling analysts to work with datasets spanning billions of rows without disrupting operational systems.

The difference between a database and a data warehouse is not a matter of scale or technology choice. It is a difference in intent. One exists to execute the business correctly in the present. The other exists to explain the business accurately over time.

2. Data scope

Another practical distinction lies in how each system treats time. Databases focus on representing the current state required for application logic. While historical data may be retained, it is typically not structured to support consistent long-term analysis without additional effort.

Data warehouses are explicitly time-variant. They preserve historical snapshots and changes over extended periods, enabling analysis of trends, seasonality, and performance evolution. This historical depth allows organizations to compare results across reporting periods using consistent definitions rather than reconstructing past states as needed.

3. Data structure

This divergence in workload is reflected in how data is modeled. Databases typically use normalized schemas to distribute data across multiple related tables, reducing redundancy and preserving data integrity. This structure supports efficient writes and precise updates, but it increases query complexity when large volumes of data must be joined for analysis.

At the same time, data warehouses adopt denormalized or partially denormalized models, most commonly dimensional schemas such as star or snowflake structures. Metrics are stored in fact tables and enriched with descriptive attributes in dimension tables. This approach simplifies analytical queries and reduces join complexity, allowing reporting and analysis to scale more predictably as data volumes grow.

4. Access patterns

These design choices shape how the data warehouse vs relational database systems are accessed. Databases are built to support high levels of concurrent access, with thousands of users or processes reading and writing data simultaneously. Availability requirements are correspondingly strict, as downtime directly affects operational continuity.

Data warehouses typically serve a smaller, specialized user base. Analysts, reporting tools, and planning systems run resource-intensive queries that can tolerate controlled execution times and scheduled data refresh cycles. Availability expectations remain high, but maintenance windows and batch ingestion processes are commonly part of normal operation.

5. Performance priorities

Availability requirements further reinforce the separation. Operational databases are expected to remain available at all times, since downtime directly affects business operations. Performance tuning centers on fast writes, efficient indexing, and stable behavior under load.

Data warehouses place greater emphasis on analytical performance and consistency. Scheduled data ingestion and maintenance windows are common, reflecting that analytical workloads can tolerate controlled update cycles in exchange for reliable, well-structured data.

Viewed together, these differences explain why analytical database vs data warehouse behave so differently under analytical load, even when they store related data. Each system encodes a distinct set of assumptions about time, usage, and responsibility. When those assumptions are respected, the architecture remains stable. When they are blurred, issues tend to surface in performance, reporting consistency, or decision confidence.

|

Dimension |

Database |

Data warehouse |

|

Primary purpose |

Support day-to-day business operations by recording and maintaining transactional data |

Support analysis, reporting, and decision-making across the organization |

|

Primary users |

Applications, operational systems, and users interacting with products or services |

Analysts, reporting tools, planning systems, and leadership |

|

Type of truth |

Operational truth reflecting the current state of a system |

Analytical truth reflecting consistent meaning over time |

|

Historical depth |

Limited and incidental; focused on the latest state unless explicitly designed otherwise |

Core capability; preserves historical data to enable comparison and trend analysis |

|

Risk when misused |

Performance degradation, data contention, and instability of operational systems |

Misaligned metrics, inconsistent reporting, and loss of confidence in analytics |

|

Impact on decision quality |

Suitable for immediate, local decisions tied to execution |

Suitable for cross-functional, strategic, and long-term decisions |

How do data warehouse vs database coexist?

Databases and data warehouses complement one another because they address different problems at different stages of the data lifecycle. Their relationship is neither hierarchical nor interchangeable. It is structural. Each system takes responsibility for a specific phase of data creation, stabilization, and interpretation, allowing organizations to scale operations and analytics without forcing one system to compensate for the other's limitations.

- At the operational edge, databases capture events as they occur. They record transactions, enforce constraints, and maintain the current state required for applications and business processes to function correctly. This layer is tightly coupled to execution. Changes occur continuously, data is overwritten as the state evolves, and performance is tuned to support high concurrency with predictable latency.

- Once operational data needs to be analyzed beyond its immediate context, the data warehouse comes into play. The warehouse does not replace the database or mirror it in real time. Instead, it consumes selected data from operational systems and transforms it into an analytical structure to support reporting, historical analysis, and planning.

This coexistence of data warehouse vs operational database is facilitated by controlled data movement. Data flows downstream from databases into the warehouse through structured ingestion processes. During this step, data is standardized, validated, and aligned across sources. Analytical models built on top of the warehouse remain consistent even as operational schemas, applications, or platforms change.

When data warehouse vs database coexist in this structured way, each system operates within the constraints for which it was designed. Operational systems remain stable under load. Analytical systems retain historical depth and consistency.

Two-speed principle for operational database vs data warehouse

In practice, many organizations adopt a two-speed data architecture to balance execution and analysis without forcing trade-offs. In this model, transactional database vs data warehouse operate at different speeds by design, each optimized for a distinct class of workloads.

- Transactional databases are tuned for immediacy. They support rapid product iteration, real-time customer interactions, and continuous operational updates. Low latency, high concurrency, and strict consistency are prioritized so that applications remain responsive under constant load.

- Data warehouses operate at a different cadence. They prioritize stability, historical completeness, and analytical consistency. Data is accumulated, reconciled, and structured to support reporting, financial transparency, and long-term analysis

A retail environment illustrates the separation between data warehouse vs database. Transactional databases record each sale as it occurs across individual stores and track updates to inventory levels, payments, and receipts. At the same time, a centralized data warehouse aggregates sales data from all locations over extended periods. This foundation consolidated historical view supports analysis of purchasing patterns, regional performance, and long-term demand trends, informing decisions on assortment planning, pricing strategy, and store expansion.

Other modern data architecture: Data lake

A data lake is a centralized storage environment designed to ingest and retain large volumes of data in its raw, native format. Unlike data warehouses, data lakes do not require data to be cleaned, modeled, or structured at ingestion time. It typically stores a broad range of data types, including structured records, semi-structured event data, and unstructured content such as logs, sensor outputs, text, images, or video. Instead of enforcing structure up front, they use a schema-on-read approach, where structure is applied only when data is accessed for a specific analytical or experimental purpose.

Because of this flexibility, data lakes are commonly used as:

- Ingestion layers for high-volume operational, event, or streaming data

- Foundations for data science, machine learning, and AI workloads

- Exploration environments where the data value is not yet fully defined

Data warehouse vs data lake vs database: What each is designed for

While data warehouse vs database vs data lake systems store data, they are designed around different assumptions about structure, usage, and responsibility within the data lifecycle.

Operational databases

Operational databases support the execution of business processes. They record transactions, enforce constraints, and maintain the current state required by applications and services. In practice, operational databases deliver the most value in transaction-heavy scenarios such as digital commerce, financial systems, and customer-facing platforms where correctness and response time are non-negotiable.

- Optimized for OTP

- Structured using normalized schemas to preserve consistency

- Enforce ACID guarantees for correctness under concurrency

- Designed for high availability and low-latency writes

- Serve applications and operational users

Data warehouses

Data warehouses are designed to support analysis, reporting, and decision-making across the organization. They integrate curated data from multiple operational systems and preserve historical context. Data warehouses create the greatest business impact in organizations that depend on cross-functional reporting, financial consolidation, forecasting, and performance management across time and systems.

- Optimized for Online Analytical Processing

- Store reconciled, time-variant data with consistent definitions

- Use dimensional or partially denormalized models

- Favor read performance and large-scale aggregation

- Serve analysts, reporting tools, and planning processes

Data lakes

Data lakes occupy a different position. They prioritize flexibility over structure and serve as long-term repositories for raw data that may later be refined, modeled, or selectively promoted into analytical systems. Data lakes are most beneficial where large volumes of diverse data need to be retained for experimentation, advanced analytics, or machine learning, particularly in product development, IoT, and data science-driven environments.

- Accept data in raw or minimally processed form

- Support schema-on-read access patterns

- Store structured, semi-structured, and unstructured data

- Scale cost-effectively to huge volumes

- Serve data engineers, data scientists, and ML pipelines

They are not designed to replace data warehouse vs database, but to complement them where raw data retention and experimentation are required.

|

Dimension |

Database |

Data warehouse |

Data lake |

|

Primary purpose |

Execute transactions |

Analyze and report |

Retain raw data |

|

Data structure |

Highly structured |

Structured and modeled |

Raw, flexible |

|

Time orientation |

Current state |

Historical |

All stages |

|

Processing focus |

OLTP |

OLAP |

Exploratory/analytical |

|

Typical users |

Applications |

Analysts, BI |

Engineers, data scientists |

|

Governance need |

Strong |

Strong |

Critical |

Get ahead with the right data architecture for you

A durable data foundation starts with clarity. Which systems are responsible for execution? Which ones are responsible for analysis? How data moves between them, how meaning is preserved, and where historical truth is established. Getting this right early reduces rework later, improves trust in reporting, and prevents analytical growth from undermining operational stability.

At N-iX, this clarity is the starting point for every data engagement. We work with organizations to assess how database vs data warehouse vs data lake currently interact, where responsibilities overlap, and where gaps undermine decision-making. From there, we design and evolve data platforms that reflect real operational constraints.

If your data landscape has grown organically and questions are becoming harder to answer with confidence, it may be time to revisit the foundation. The right architecture reduces doubt and gives data a clear role at every stage of its lifecycle.

FAQ

What is a data warehouse vs database?

A database is designed to run applications by recording and updating transactions in real time. A data warehouse is designed to analyze those transactions over time by consolidating data from multiple sources into a consistent, historical view. The difference lies in workload and purpose, not in data storage alone.

What is a data lake vs data warehouse vs database?

A database supports operational execution, a data warehouse supports structured analysis and reporting, and a data lake stores raw data in its native form for future use. These systems are complementary: data often flows from databases into data lakes or warehouses, depending on whether it is needed for experimentation or standardized analysis.

Can a data warehouse replace a database?

No. A data warehouse is not built to support real-time transactions or application workloads. Using it as a replacement for a database introduces latency, consistency risks, and operational instability. Instead, operational systems should continue to rely on purpose-built databases, while a data warehouse is used downstream to aggregate transactional data for reporting, analysis, and historical comparison without affecting application performance.

Have a question?

Speak to an expert